After the summer's high profile riots in many British cities it seems fitting to bring to attention another wave of violence that took place in the same week of the summer of 1842, with a focus on the tragic events that took place in Preston, Lancashire and how it was reported by the media - and how it contrasted with media reporting of riots in 2011. In the summer of 1842, general strike began amongst miners in Staffordshire and quickly spread to other areas. In many areas plugs were removed from boilers to put factory machinery out of action - thus preventing factories from being able to open - which gave rise to the disturbances being referred to as the Plug Riots. The early to mid-nineteenth century was peppered with industrial action, as the workers in Britain's rapidly industrialising society fought back against low wages, dangerous working conditions and often tyrannical factory owners. In the early 1840s workers could still be blacklisted if discovered to be a member of a trade union - in other words, unable to work. After a damaging defeat following a spinners’ strike in 1836-7, the Lancashire cotton unions were during said to have become completely inactive due to the harsh crackdown on union activity.

[1] Many political groups pressed for change. Among these causes was that of the Chartists, who campaigned for a People's Charter demanding universal male suffrage and fairer, more democratic elections. In 1842, a petition with 3,315,172 signatures demanding the Charter had been rejected by Parliament and tension was high.

[2]

Preston was a hotbed of industrial unrest in the

early nineteenth century – there is evidence of agitation occurring in the town

every few years, mostly due to the boom-bust nature of the developing

capitalist economy. Preston had also had

a long association with radical politics due to its eclectic mix of gentry and

a rapidly growing working class.

Radicalism amongst members of the middle class was not unusual – the

famous Radical MP Henry “Orator” Hunt represented Preston between 1830 and

1833. The developing factory system

which spread through Lancashire’s towns in the early nineteenth century

“depersonalised” the workers and gave them far less control over their

employment than the previous cottage industries and small-scale manufactories

that preceded the factory movement.

The “Great” Reform Act of 1832 had also had

the unusual effect in Preston – before the Act was passed, any man who paid

taxes was eligible to vote, giving Preston an uncommonly wide voting franchise

compared to other areas, representing almost the entire male social spectrum in

the town.

The Act, however, actually reduced the number

of people in Preston eligible to vote rather than increasing the franchise.

Exact figures for Preston’s franchise at this

time are difficult to find due to the complicated, often corrupt and chaotic

nature of elections in the early nineteenth century (one of the reasons the Act

was passed in the first place), but as the Act decreed that only those paying

more than £10 a year in rent were eligible to vote, one can assume that in a

town such as Preston, with a sizeable working class, this probably meant that quite

a significant number of people lost the right to vote. It was arguably this type of disenfranchisement

that added fuel to the Chartist movement, which had been founded on the belief

that the 1832 Reform Act did not make elections democratic or fair enough.

|

| Cotton Factories in Preston, date unknown - © Harris Museum and Art Gallery, Preston | | | | |

|

Opinions differ wildly over how involved the

Chartist movement was in the Plug Riots that swept through much of the North of

England during the summer of 1842. One thing that can be certain is that

the terrible tragedy that occurred when the striking reached Preston sent

shockwaves through the town and very likely put a great deal of people off any

further confrontational activity. One

problem when it comes to interpreting exactly what happened in Preston on 13th

August 1842 is that there are very few surviving primary sources that give an

objective view of events.

The

Preston

Chronicle reported, in an article entitled “Preston Riots: Firing upon the

people”, that a mill on North Road, close to the town centre, had been attacked earlier in the morning of

13th August and that “some damage [was] done to the outside of the

mill.”

The report goes on:

“

At about

eight o’ clock, as the mob were proceeding up Lune-street, near the New Market,

they were met by a body of policemen and the military. The crowed commenced shouting and throwing

stones. On Captain Woodford making

towards them, as if to arrest one of the parties, he was knocked down. One of the constables in endeavouring to

assist was struck a violent blow on the arm with a stick, and on the chest and

in the face with stones. An attempt was

made to reason with the parties, and they were informed that if they did not

disperse, and cease their riotous conduct, orders would be given to fire upon

them. The Riot Act was read, and the

police having been beaten back, the order to ‘fire’ was given, and several were

wounded... We hear that eight have been wounded – five mortally. Notice has been posted on the walls that the

Riot Act has been read.”

The

Chronicle

also printed reports of disturbances in other industrial towns in Lancashire,

and noted that “parties suspected, if not known, to have come from Manchester

and Bolton, were busy in [Preston] on Thursday evening.”

Given the nature of the Plug Riots and the

way that they spread rapidly from town to town it is possible that agitators

were travelling around trying to stir up other workers, although the

Chronicle’s claims are unsubstantiated

and confined to a small paragraph at the end of a longer report. Perhaps in an attempt to claw back a little

civic pride the

Chronicle was

trying (admittedly rather half-heartedly) to pin the blame on

non-Prestonians.

However, what seems to have been established as fact is that following the gathering of a large number of workers on Lune Street in the centre of Preston on 12th August 1842, the Mayor, Samuel Horrocks (part of a famous cotton factory-owning family), read out the Riot Act. Passed in 1714, the Riot Act allowed local authorities to disband any gathering of twelve or more people that they perceived to be causing or likely to cause disturbances. If those gathered failed to disperse, the Act authorised the use of force to remove people from the area. This is what came to pass in Preston. The military mentioned in all newspaper reports was the 72nd Highlanders, who were at that time stationed in the town. The

Preston Pilot reported:

“Immense bodies of stones were now thrown at

the police and soldiers, many of the former being much hurt, and a party of the

mob having gone up Fox-street, they then had the advantage of stoning the

military from both sides. Under these circumstances, orders were given to fire,

and immediately obeyed, and several of the mob fell. This did not appear to

have much effect.”

|

| The (possibly) only contemporary illustration of the Lune Street shooting, London Illustrated News, September 1842 |

The lack of any real alternative to the media reports of the Preston shootings is problematic – there are few surviving eyewitness accounts of the violence outside of what was reported in the media. If diaries detailing eyewitness accounts exist, they have not come to light, and histories of Preston carrying details of the event appear to have got all of their information from newspaper reports. The newspapers carrying reports of the events were published on the same day, providing an example of how, even in those days, news could be printed and distributed very quickly. In the case of the local press, newspapers reporting the violence were for sale only a few hours after what had happened, which is comparable to the turnover of printed newspapers today – although today stories can appear almost instantly on newspapers’ websites.

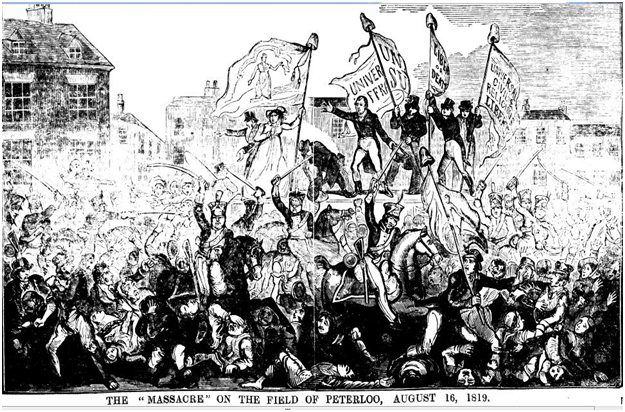

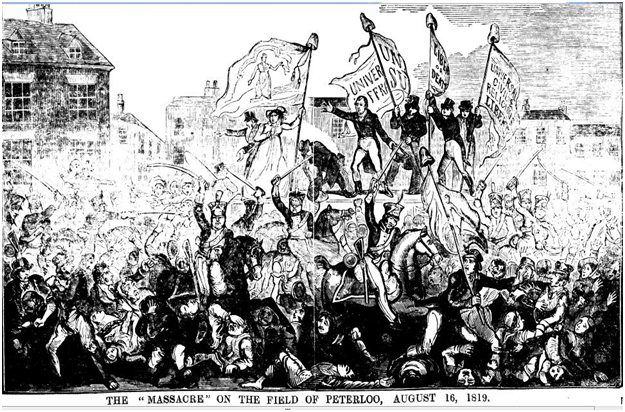

The Northern Star provides historians with perhaps the one alternative viewpoint to the bloody events in Preston. A Chartist newspaper, owned by Feargus O'Connor, the Star was published in Leeds and published impassioned coverage of Chartist events up and down the country as well as printing a great deal of letters from supporters of Chartism. An image on the front page of an edition of the Northern Star published soon after the riots in Preston (described by the paper as "horrible carnage") depicted the infamous Peterloo massacre of 1819 – drawing parallels, perhaps, between the two events.

[10] The other publications covering this event do not look to the history books - their reporting was more concerned with the particulars of what had happened, seeking to provide details rather than to place the event in any historical context. This contrasts quite sharply with the reporting of the August 2011 riots, when comparisons were drawn up with unrest in the 1980s at Broadwater Farm, Brixton and Toxteth, and some reporting even hearkened back to more distant events such as the Gordon Riots of 1780.

|

| From the front page of the Northern Star, 20th August 1842 |

Although the Northern

Star was a Chartist paper and therefore more sympathetic to the working

classes (although many parts of the movement strongly opposed the use of

violence), Preston’s media was owned by the town’s elites, most of whom had

become wealthy through the cotton industry.

Therefore it is reasonable to assume that the reporting in the Preston-based papers would have been

biased to a greater or lesser extent towards the sympathies and political views

of the mill owning class. Similarly, the picture from the London Illustrated News, shown earlier in this post, uses language such as "attack on the military" and "rioters", again suggesting a viewpoint less sympathetic towards the cause of those wounded and killed. Even the Northern Star, however, stops short of condoning the more confrontational actions of those workers gathered in Preston that day. Interestingly, the context of the Plug Riots and the reasons why the workers of Preston were angry were not explored by the media (with the exception of the Star) - a contrast to the soul searching by many newspapers, commenters and blogs after the riots of August 2011.

On paper at least, Preston seemed to move on from

the shootings fairly quickly – although of course the suffering and grief of

those injured, killed or otherwise affected by the bloodshed was not

chronicled. Preston’s Guild celebrations

were held in the first week of September.

It was not the last time that the Guild would be overshadowed by grim

events during the Victorian period – the following Guild in 1862 went ahead

despite great unemployment, hunger and suffering caused by a cotton shortages brought about by the American Civil War.

However, there is a lasting – and more sympathetic – memorial to those killed on 13th August 1842. A large group of statues were unveiled on Lune Street, on the site where the disturbances turned bloody. These statues depict cowering and frightened workers being shot at by a row of soldiers.

The

inscriptions on the monument read as follows:

In Lune Street, Preston, four workers

were shot and killed by the military during the General Strike of 1842.

Several thousand Preston workers were

demonstrating against wage cuts and for the ‘Charter’ of democratic rights.

Remember, remember, people of Proud

Preston that progress towards justice and democracy has not been achieved without

great sacrifice.

Remember, remember, people of Proud

Preston to defend vigorously the rights given to you, strive to enhance the

rights of those who follow.

These

thought provoking words seem timely given the amount of “shoot the rioters”

rhetoric that sprang up in the aftermath of the riots in English cities in

August 2011. No records remain of what

happened to the families of those killed and injured in the Lune Street

shootings, but during this period the workers of Preston and other industrial

cities had few rights and their survival was at the mercy of a fluctuating

labour market where frequent overproduction during times of plenty led to lean

periods where thousands struggled to find work.

Preston’s

industrial struggles did not end with the events of 1842, although later in the

1840s the town enjoyed a period of relative prosperity following the arrival of

the railways. But in 1854 the decision

to cut the wages of cotton operatives led to a long and bitter struggle between

worker and employer that became known as the “Great Lock-outs”.

Although, thanks to a limited amount of surviving evidence, we may never get the complete story of what happened on Lune Street on 13th August 1842, studying the remaining evidence - that of media reports - provides a fascinating insight into how reporting of such events has changed. As in 1842, the media of 2011 has its own agendas and political leanings, but present-day reporting contains a great deal more analysis and opinion pieces than the newspaper reports of 1842. The Victorian newspapers, barring the Northern Star, fail to place the Lune Street shootings into much context - both in the context of industrial relations at the time, and in a more historical context. This lack of context makes it difficult to understand the actions of both the crowd that was shot at, and those giving the orders to open fire - the reporting of the August 2011 riots, on the other hand, will provide historians of the future with a broader view of what contemporary eyewitnesses and more distant observers thought of the disturbances, although it's also true that these historians of the future may be completely overwhelmed with the sheer volume of sources surrounding the 2011 riots - but that's another story.